When Athletes Were People, Too

The Cloud Yeller: A site for anyone who's tired of reading about things that actually matter.

I met the winner of a beauty pageant once. At the time, it didn’t seem like a significant moment. Looking back now, however, it may have been one of the formative experiences of my life.

Way back in the late 90s, my college social club volunteered to work the phone banks at the local Memphis broadcast for the (now defunct) Jerry Lewis Muscular Dystrophy Association Labor Day Telethon*. As upstanding, civic-minded, self-sacrificing college students, a few friends and I participated (full disclosure: We also received free admission to the (now defunct) Libertyland amusement park for volunteering).

Clearly, the event organizers were unaware of my phone-answering prowess, as, unfathomably, they did not assign us to work one of the prime-time slots. I can’t remember what slot we worked, but it wasn’t where any of the more famous local celebrities showed up. In fact, the “celebrity” phone answerer working in our time slot was Little Miss Libertyland. When I was eight, I’m pretty sure I was intimidated by college kids. Eight-year-old Little Miss Libertyland was not.

As you may imagine, when you work a phone bank where a pre-teen beauty queen is the “celebrity,” the phones were not ringing off the hook. In trying to pass some of this downtime, a friend asked Little Miss Libertyland about her crown (“LML” was dressed in full pageant attire, complete with poofy dress, sash, and crown). She proceeded to inform us in no uncertain terms that it was, in fact, not a crown, but a tiara and that we were not allowed to touch it. Over the next hour, LML would go on to insult us with mean-spirited comments on both our appearances and intelligence. Honestly, it was pretty amusing.

As a result of this encounter, however, I came to the conclusion that beauty queens are not like the rest of us. Perhaps because they have been competing, performing, undergoing interviews, and getting judged for their entire lives, they’re not allowed to just be “regular people.” They don’t understand the common folk, and at the same time, we can’t understand them.**

*As a kid, I hated the Labor Day Telethon because it took up an entire channel for the entire day. When you only have about six channels, you can’t afford to give one for a boring telethon. Sadly, the MDA telethon was scaled back starting in 2011 and discontinued entirely in 2014.

**Obviously, this is a generalization and does not apply to all pageant contestants. As noted above, my interactions with beauty pageant winners have been extremely limited. But if there is a community of past beauty pageant winners, know that 1990-something Little Miss Libertyland is giving you all a bad reputation.

The same thing is happening in athletics. As more and more money begins to flow in to athletes at earlier and earlier ages, like beauty queens, it will be harder and harder for these athletes to identify with us commoners.

Of course, star athletes have been elevated and mythologized for years. Placed on a pedestal as if sculpted by an ancient artist. The hagiography goes back centuries. The Greek poet Pindar wrote a poem for Olympic-champion boxer Diagoras of Rhodes in 464 BC. (Diagoras’ three sons also won Olympic wreaths, becoming the precursor to today’s Manning family).

The difference, however, is that whereas athletes were previously revered and compensated based on their accomplishments, it’s now become prevalent (and legal) for “amateur” athletes to be compensated primarily for their potential.

As you’ve likely heard, the House Settlement recently received judicial approval.* If you’re unfamiliar, the approval of the settlement brought an end to the House v NCAA lawsuit, with the NCAA and other defendant athletic conferences agreeing to pay $2.7B in backpay to college athletes competing between 2016 – 2024 and then allowing for each school to pay up to $20.5M to current athletes. This AP article is a nice summary if you’re interested in more details.

*Almost immediately upon approval other parties sued to stop the settlement, including multiple lawsuits that claim the settlement violates the non-discrimination requirements of Title IX, as the settlement allows schools to make higher payments to the sports that bring in more money (generally football and men’s basketball). So, it may not be settled after all. We’ll see.

The House settlement is yet another leap into the professionalization of college athletics, leading to more athletes making big money at an earlier age. I understand that many college athletes have been undervalued and prevented from capitalizing on their own marketability by archaic, but (presumably) well-intentioned, NCAA rules. I’m not arguing that athletes making money is unfair. I’m just concerned with how the NCAA, courts, and Congress will balance “fairness” with the actual best outcome for students and athletes. And if it’s even possible to determine such a balance (especially when Congress is involved).

We’ve already flown past the concern that money will filter down to high school athletes. As noted in this MSN article, there’s a middle school football team in Washington D.C. with at least four players getting paid through Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) deals. The coach has started teaching his middle school kids how bank accounts work (not to imply that this knowledge is a bad thing). Nike has signed kids as young as 13 to NIL deals. That’s a long way from my days of playing Oregon Trail on an Apple ii as a middle-schooler.

As the money increases, so does the pressure to maintain and perform. This website ranks the top travel baseball teams in the nation, including a list of the top 50 teams for kids aged eight and under. As someone who always loved sports but was never good enough to be any better than average (being generous), the concept of seven- and eight-year-olds traveling nationwide for baseball games boggles my mind. The idea of adults taking it so seriously as to rank the top 50 teams is even more puzzling.

Again, even though I can barely comprehend it, I’m not debating the merits or massive resources required for travel sports (although something seems off when Hollywood stars are having to solicit Go-Fund-Me donations for their kids’ travel teams (I’m looking at you, Samantha Micelli from Who’s the Boss).

I’m left wondering whether it’s really beneficial for kids to become professional athletes as middle and high schoolers. We’ve arrived in an era where we value our athletes so highly that we’re paying 14-year-olds to play sports. Is it too much pressure too soon? Do eight-year-olds feel like their lives are ruined if they don’t make a top travel team? Do they ever just get to be kids?

It’s a conundrum: If someone’s willing to pay a kid to play sports, then it’s great for the kids. On the flip side, there’s enough pressures in today’s world without kids feeling the weight of earning a paycheck from their athletic performance.

Society’s been heading down this path of athletic elitism for a while. In 1987, science fiction author Robert Heinlein* wrote,

“The United States had become a place where entertainers and professional athletes were mistaken for people of importance. They were idolized and treated as leaders; their opinions were sought on everything and they took themselves just as seriously — after all, if an athlete is paid a million or more a year, he knows he is important … so his opinions of foreign affairs and domestic policies must be important, too . . .”

*Heinlein said a lot of stuff. A lot of it I don’t agree with, but some of it resonates, like “Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity.” I suppose it’s better to assume a lack of intelligence than simple meanness.

With high school athletes signing million-dollar contracts, are we creating a new generation with an inflated sense of importance? I don’t know. It’s possible I’m still feeling the scars from the insults of an eight-year-old pageant queen. Maybe I’m just jealous.

Regardless, I do know it wasn’t always the case. There was a time when athletes were regular people too. You can see the transformation just in looking at sports cards.

This is Tom Brady’s 2022 Panini card. Brady retired in 2023 at the age of 45. He was still in great shape and performing at a high level.

Brady recently posted a workout photo. Still seems to be in pretty good shape at 47. In fact, he looks like he was created in the same lab that gave us Ivan Drago in Rocky IV (minus the steroids, of course).

This is George Blanda’s 1975 card, at the tail end of a Hall of Fame career as quarterback and kicker.

Blanda played forever – starting in 1949 and playing his last game in January 1976. He was a great player and great athlete, but he looked like what he was – a 48-year-old playing football.

From my era of fandom, Charlie Hough was one of the Rangers best pitchers in the 80s (unfortunately, while that’s a pretty low bar, he’s still the Rangers all-time leader in wins). Known for his knuckleball (he once said, “I throw 90 percent knuckleballs, the other 10 percent are prayers.”), Hough pitched in the majors for 25 seasons, ending in 1994 with the Florida Marlins (he was the winning pitcher in the Marlins first-ever victory in 1993). He’s the only pitcher to make 400 appearances as a reliever and make 400 starts. He had a great career, but he, too, looks like what he was – a 46 year old man.

No one looking at that card would think major league pitcher. Manager, maybe. Perhaps an ex-player showing up for an old-timers game. But not someone who pitched over 100 innings in the majors that year. Now, scroll back up and take another look at 47-year-old Brady. Which 40-year-old athlete’s pregame ritual do you suppose included a cigarette and a crossword puzzle?

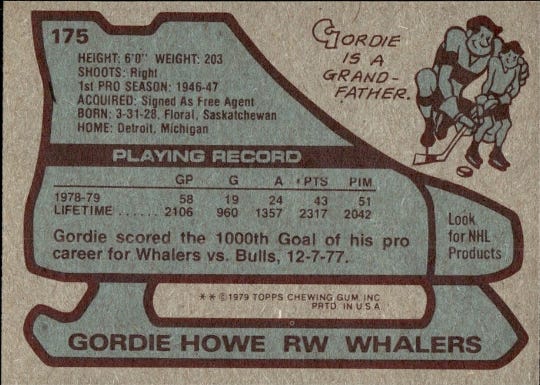

My favorite “old-player” sports card may belong to “Mr. Hockey,” Gordie Howe. Howe was playing in the NHL into his 50s, which is amazing.

It’s ok that he looked like a grandfather out on the ice, because when you turned his card over, you found out that he was a grandfather.

It’s not just the old guys that were more regular people-ish. Here is John Kruk’s 1987 rookie card:

Kruk was a three-time All-Star and a career .300 hitter over his 10 year career. You could make a Hall of Fame case for Kruk. I loved John Kruk because he was a pinch hitter on the NL All-Stars (my preferred team) on our Nintendo version of RBI baseball with his 1987 stats. Unfortunately, he also kind of looks like the real-life model for the players in that version of RBI:

On the back of Kruk’s rookie card, we learn, “John attended Allegheny Community College.”

I miss those “fun facts” on the backs of sports cards. In fact, it’s one of these “fun facts” that really helps explain the change in athletes over the past 50 years.

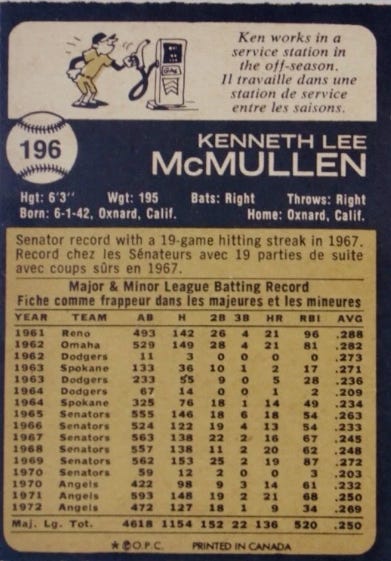

“Ken works in a service station in the off-season.”

When a 10-year veteran has an offseason job at a service station, you know it was truly a different era. Athletes in earlier eras seemed more like regular people because they were more like regular people. It’s pretty bizarre now, but many athletes had to have offseason jobs to support their families.

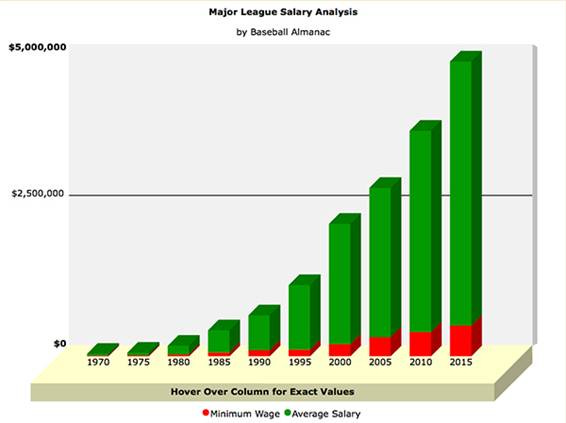

This graph from baseball-almanac.com is telling:

Baseball’s minimum annual salary in 1970 was $12,000 (the equivalent of $100,000 today). That’s above average, but not rich by any means. On the graph, it’s so low you can’t even see the red line. The minimum salary for 2025 is $760,000. There’s no need for an offseason job making that kind of money. Today’s players can spend the offseason training physically and mentally, as well as healing their bodies from the season’s grind.

But, back in the olden days, athletes were selling appliances and pumping gas rather than pumping iron. It wasn’t just the average players that had regular jobs, either. All-Stars were working in the offseason as well. While the additional money was helpful (and sometimes necessary for the players), occasionally they worked because it was a field they enjoyed or because they needed something to pass the time between seasons. Our culture had not yet come to the realization that professional sports were so important that athletes needed to train year-round.

The Cloud Yeller Athlete Regular Job Challenge:

In the interest of highlighting just how “regular” some of these offseason jobs were, see if you can match the professional athlete with his offseason employment:

Answers at the bottom of the article. Feel free to post your results in the comments.

I’m sure none of these athletes would want to go back to the “good” old days when they needed a second job and were relieved when/if they made enough from sports to not have an offseason job. Certainly, today’s athletes are better from being able to focus on training and health during the offseason. And while I appreciate the improvements to sports brought about by year-round training and I’m in favor of athletes being paid what the market will support, it’s hard not to feel a little nostalgia for the time before middle-school NIL deals. Back to the time when athletes were people, too.

The Cloud Yeller’s Complaint of the Week:

In the 80s and 90s, movies promised us an array of technical advancements that we’ve yet to see. This really came to our collective awareness in 2015, the year of “the future” in Back to the Future II. We were promised flying cars, hoverboards, and engines run by “Mr. Fusion.” We have none of those. (I know we have things called “hoverboards,” but those are poor excuses compared to what the movie promised.)

Yet the movie technological advance I believe we’re most lacking is not from Back to the Future, but rather from Christmas Vacation. You may recall that Chevy Chase’s character Clark Griswald was a food additive designer and had developed the “Crunch Enhancer,” a non-nutritive, semi-permeable, non-osmotic cereal varnish that coats and seals the flake, preventing milk from penetrating and eliminating soggy cereal.

As anyone who has recently endured the last few bites at the bottom of a bowl of Frosted Flakes can attest, this promised future of continual crunchiness has not been manifested. It’s time that we, as soggy-cereal weary consumers, rise up and demand that more research and development be invested in the things that really matter. Into inventions that will improve the lives of untold millions. Inventions that will keep our cereal firm against the tyranny of sogginess.

It’s time to demand the Crunch Enhancer.

Regular Job Challenge Answers:

1. Nolan Ryan: E - Air conditioner installation. As Jim Caple said in the article, Hall-of-Fame pitcher Nolan Ryan “brought the high heat in the summer [and] evened things out by installing cool air in the winter.”

2. Lou Brock: D – Owned a flower shop. The Hall of Fame outfielder for the Cubs and Cardinals was quoted as saying, “It’s a rough business. You’ve got to give ‘em what they want.” He wasn’t talking about his baseball career, but rather his time as the owner of a successful flower shop. Brock also licensed and sold the “Brockabrella.”

3. Jim Palmer: A – Men’s clothing salesman. In 1966, future hall-of-famer Palmer threw a complete game shut-out in game 2 of the World Series. After the Orioles beat the Dodgers in World Series that year, Palmer went to work at Hamburgers Clothing in Baltimore, making $150 per week to help pay for his new house and renovations.

4. Waite Hoyt: H – Funeral director. Hall of Fame pitcher for the Yankees in the 1920s worked as a funeral director for his father-in-law. In addition to his more famous nickname, “Schoolboy,” Hoyt was also known as “The Merry Mortician.”

5. Stan Musial: I – Owned a Christmas tree lot. The Hall-of-Famer Stan “The Man,” owned a Christmas tree lot with other St. Louis Cardinals.

6. Lou Groza: J – Insurance salesman. Lou “The Toe” Groza played offensive tackle and kicker for the Cleveland Browns, retiring in 1968 at the age of 44.

7. Johnny Unitas: C – According to NFL Films Steve Sabol, Johnny U once laid linoleum during the offseason at teammate Raymond Berry’s house.

8. Mordecai Brown: F – Coal miner. Brown was nicknamed “Miner” for having worked in the coal mines, especially prior to his baseball career. His other nickname, Mordecai “Three-Fingered” Brown is more interesting, however.

9. Oscar Robertson: B – Construction. The Basketball Hall-of-Famer worked construction as a day job prior to winning a basketball gold medal in the 1960 Olympics.

10. Roger Staubach: G – Real estate broker. Captain America worked as a commercial real estate broker in the NFL offseason. He started his own firm, The Staubach Company in 1977, leading to his current estimated net worth of $600M.

11. Ray Wershing: K – Public accountant. This one was a bonus, only because I wanted to include athlete who was a CPA in the offseason. Wershing was a long-time kicker for the Chargers and 49ers in the 80s. He was later indicted for embezzlement and pled guilty to failure to file a corporate tax return. So much for the public trust in CPAs.